Say the Thing.

“We have a moral obligation to tell the truth. Tell the truth even when our voices shake. Tell the truth even when it might rock the boat. Tell the truth even when there might be consequences. Because that in itself makes us more courageous than most people in the world.”

As an organization of former and current educators and leaders, we at 2Revolutions are consistently engaging in the difficult conversations and training for a constant cycle of improvement. When you are in the education world, you know there is never a point in time when you do everything exactly the right way, and when you have learned everything possible. There is always room for growth and things that need to be learned, unlearned, enhanced and changed. We all are human first and we all have flaws. A diamond with a flaw is more valuable than a brick without a flaw. What are you allowing to weigh you down? Throughout the last couple of months, a trend has emerged in our conversations, in our partner meetings, in planning for our internal development sessions, and amongst our coaching staff: that trend is where the title comes from for this piece. “Say the thing.”

We believe that strong self-awareness is at the heart of strong leadership. We started the piece with a quote from Luvvie Ajayi Jones from her book, Professional Troublemaker. This excerpt puts a stamp on the concept that saying the thing, whether it is difficult to say, or may hurt someone’s feelings, is important. Often it is even necessary to say the thing to yourself. But, most importantly when dealing with teachers, school leaders, district leaders, education organizations and government officials charged with creating educational policy, saying the thing is a requirement. John Lewis once said, “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have a moral obligation to do something, to say something, and to not be quiet.” Educational policy right now is on shaky ground in many places, and some things need to be said. Whether red, blue or purple, what side of history do we stand on? If we don’t say them to our leaders, our coaches, our people in the field each and every day, who will? If we don’t say them, who will speak up for our children, our learners, our future?

In a text on “White Supremacy Culture” the Minnesota Historical Society addresses this idea of a “Right to Comfort.” This idea that there is a belief that those who have power or those who are leading have “a right to emotional and psychological comfort.” This concept equates to not wanting to point out flaws or issues in the system in hopes that no one’s feelings get hurt. Our world perpetuates this culture, so many leaders of schools, districts and organizations get away with saying things and doing things that don’t feel right to all involved. Why? No one wants the conflict, the hurt feelings or to take the risk of retaliation.

There are some things that we can control and change in our individual daily experiences, and some that we cannot. We cannot alter the culture of society with one article or one request. That’s impossible. However, as we work to train and educate school leaders and educators through our graduate program and communities of practice, we can start to have a larger impact that will hopefully translate into the districts and the schools those people work with in the future. We just have to “say the thing.” Leadership whether “l” or “L” has afforded many leaders an opportunity to reflect on how one’s vision, priorities and approach set a clear tone for a school and profoundly shape the experiences of the children and families they serve.

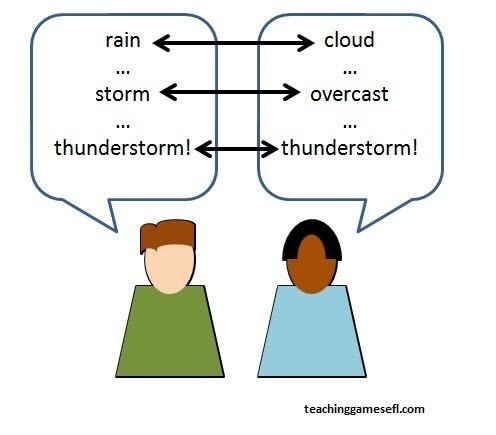

Sometimes it is hard to give difficult feedback and have the necessary conversations. It is important that the feedback is grounded in data. We want to share an example of using a framework to ground one's feedback in data, which is a clearer, and sometimes easier, way to ensure there is consistent grounding in an equitable vision, without having to give a different purpose each and every time for the feedback. In partnership with Spalding University, through their participation in the Wallace Equity Centered Principal Pipeline Initiative (ECPI), we co-constructed a framework of six core principles that ground our work and growth in equitable educational leadership practices.

Our goal is to ensure that leaders who emerge from the Spalding University Aspiring Leaders program have an equitable “mindset and skill set” that equips them to lead both educators and students in a system of education that is rigorous as well as fair and focused on the skills necessary to excel in a diverse society. Spalding’s Equity-Centered Leadership Framework (the “Spalding 6”) serves as a consistent measure of equitable educational leadership practices and reflects the journey that an aspiring, equity-centered school leader educator takes to develop and refine these practices.

The Spalding 6 dispositions are:

Implement rigorous and inclusive academic and student support programming;

Ensure equitable talent and operational management practices;

Disrupt power imbalances and systemic oppression in schools;

Leverage support from district, school, and community partners;

Engage in self-reflection for personal and professional leadership development; and

Promote accountability through continuous improvement to ensure equitable outcomes for students.

The six principles outlined in the Spalding Six framework are grounded in the tenets of cultural humility, a framework developed by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia (1998) to educate healthcare workers to work with diverse patient populations. To be culturally humble, an individual must engage in a life-long journey to learn about cultural differences and constantly self-assess their individual interactions with others, have a sincere desire to actively address power imbalances, and work to develop alliances with others who advocate for marginalized individuals and groups. While the culturally-competent school leader has a wide knowledge base of information regarding individuals from different cultures and backgrounds; the culturally humble leader is interested and curious in learning about others, willing to identify, conceptualize, and confront individual and group biases, and holds their individual school, institution and district accountable for outcomes for all.

When developing the framework with the 2Revolutions team, the College of Education faculty at Spalding University collaborated with various community partners to gain feedback and input to develop the six leadership dispositions. These partners included Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS)- the district partner in the Wallace ECPI grant, the Louisville Urban League, Evolve 502- a community organization focused on equitable educational outcomes for Louisville’s youth, and members of Spalding University’s School of Social Work. Our goal was to develop a framework used to train, develop, and support learners in their journey to become equity-centered school leaders and meet the needs of the school district and the community where our leaders will serve.

Learners in Spalding’s Principal Preparation Program use the Spalding Six as a framework that guides their year-long academic experience. Curriculum and assignments are connected to the framework, and learners are frequently asked to make explicit connections between their learning as a future school leader and the equity-centered learnings and connections associated with them. In addition, program candidates receive support from a University Coach who assists with connecting them with clinical field experiences that operate from a continuum that describes observing equity-centered leadership practices, participating in these activities, and at the highest level, leading other educators in authentic school-based activities. The program culminates with a Capstone Exhibition of Learning where each leadership candidate prepares a portfolio containing a body of evidence of their work that demonstrates the Spalding 6 leadership dispositions, a presentation of the work in front of their University Coach and Principal Mentor, and a defense of their work that describes what they have learned, how it has made them a more equity-centered leader, and what further work must be completed to fully develop their leadership preparation.

Therefore, we have the facts and the grounding at the forefront of any conversation. This allows for hard conversations not to be hard, and for us, as coaches and leaders, to be able to say the thing that is necessary to help guide the principles of these leaders before they are placed in roles in which they have the opportunity to impact and lead more and more youth. Grounding aspiring leaders in equity-centered leadership dispositions prevents situations where Luuvie Jones notes that, “avoidance has never been a great tactic in solving any problem. For most situations in life, not addressing what’s going on only makes matters worse.”

In all honesty, the first step in all of this work had to be some personal identity work, some looking back into practices we have participated in as educators and leaders, and just our internal biases based on where we are from, where we have been, and where we led. Without that integral work, feedback can often come off as angry or unsubstantiated. Luvvie Jones reminds readers, “Do you mean it? Can you defend it? Can you say it thoughtfully or with love?” Often, when it gets to the point where the THING needs to be said in our professional lives, it’s been building up. It is key to make sure that feedback is consistent enough with your schools, in your classrooms, and your organizations that you are not only expecting it, but you are asking for it. Cultural competence allows one to operate with self-awareness and seek to understand first. We show up as our authentic selves and make space for others to do the same, naming and disrupting inequity everywhere we go. We know that it’s our responsibility to constantly challenge our own identities, bias and assumptions, while believing in leading schools where children feel affirmed, valued and challenged every day.

Everyone does have the right to be comfortable, but not at the expense of others comfort. Feedback can often be hard, but the more consistent the internal work and external work is happening, the less difficult the process will be and the overall impact on the teachers and students and their learning, as well as their comfort within the school system, will be evident.

The goal is not to wait until it’s emotional, but allow “saying the thing” to be a habit for all involved in the work.